His article seemed to me a fluff piece for his own product and organization: Benetech, the makers of Martus. I’m sorry Bruce, but Patrick Ball did no better at explaining, in my opinion. I agree some tools may have been over touted in the press, but please don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. There is a security continuum and the users have to be aware of what level they need. No one can offer perfect communications security in the online world, but don’t throw out anything that doesn’t come up to the level of “perfect”. You have to match the threat with the countermeasure.Īmong a host of possible users, any victim of domestic abuse could use these systems to prevent their communications being monitored by their partner, any teenager who doesn’t want his mother reading his emails to his girlfriend, and most corporate whistleblowers would be able to safely use these types of systems. While I agree that all applications that depend on host-based security suffer from the same foundational weaknesses, to say that Hushmail is “no more secure” than Gmail or that “security in a host-based encryption system is no better than having no crypto at all” is patently false and misleading.Ĭryptocat, Hushmail, and other host-based security systems offer great security and fill a number of security needs when used for the correct applications. I thought Singal’s piece was a refreshing corrective to this mindset.

Cryptocat not working software#

Too often, computer/crypto security is discussed in absolute 1/0 terms, a framework encouraged by theoretical research into cryptanalysis and software security, which yields categorizations of “secure/insecure”, without reference to use.

For these sorts of purposes, a less impregnable solution can be acceptable, particularly if it is part of a tradeoff that yields greater ease of use for people living under this sort of threat who are not as technically-savvy as Soghoian et al. And, of course, that is the maximalist threat that informs the thinking of people in high-surveillance countries with civil rights issues, as well as cryptosec fundamentalists.īut there is another valid model for other people, along the lines of “my abusive ex-husband/boyfriend is trying to stalk me”. If your model is “the government is out to read your mail”, then no, of course you can’t rely on something like this. Stripping away the irrelevant gender-bias accusations at the beginning of Singal’s piece, I thought he was making a rather nuanced point that has been missed by much of the attending discussion: absent a realistic threat model, there can be no serious discussion of the security of a system like Cryptocat. More generally, your security in a host-based encryption system is no better than having no crypto at all.ĮDITED TO ADD (8/14): As a result of this, CryptoCat is moving to a browser plug-in model. This means that in practice, CryptoCat is no more secure than Yahoo chat, and Hushmail is no more secure than Gmail. I’ll detail it below, but the short version is if you use one of these applications, your security depends entirely the security of the host. Unfortunately, these tools are subject to a well-known attack. The most famous tool in this group is Hushmail, an encrypted e-mail service that takes the same approach.

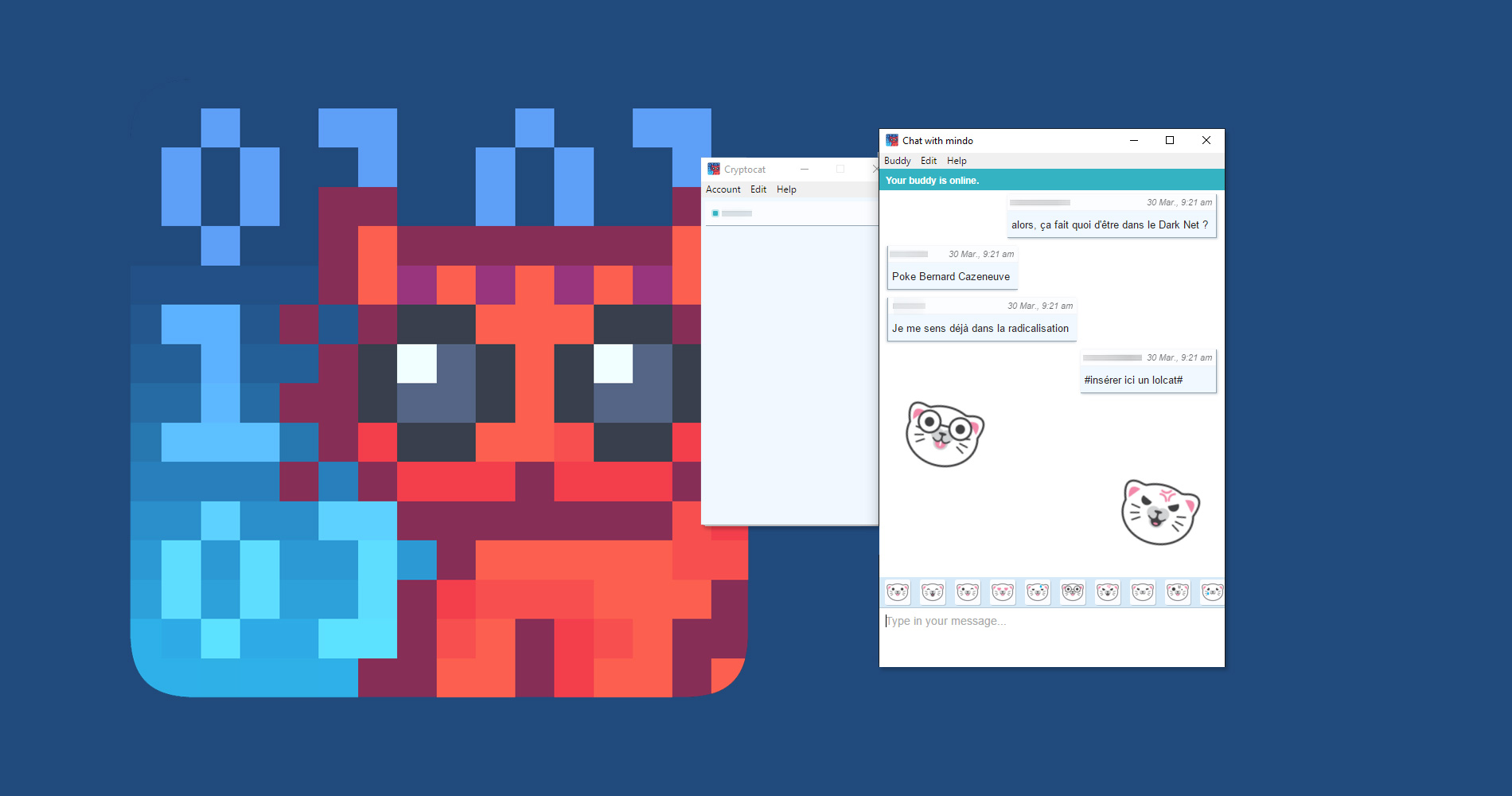

Ryan Singel, the editor (not the writer) of the Wired piece, responded by defending the original article and attacking Soghoian.Īt this point, I would have considered writing a long essay explaining what’s wrong with the whole concept behind Cryptocat, and echoing my complaints about the dangers of uncritically accepting the security claims of people and companies that write security software, but Patrick Ball did a great job:ĬryptoCat is one of a whole class of applications that rely on what’s called “host-based security”. After Wired published a pretty fluffy profile on the program and its author, security researcher Chris Soghoian wrote an essay criticizing the unskeptical coverage. Cryptocat is a web-based encrypted chat application.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)